(How does Mogherini rate her own performance? Click here to find out.)

If a 3 a.m. phone call is a defining test for a prime minister or president, for Federica Mogherini it’s a half-awake version of hell. As the European Union’s chief diplomat, she can speak for herself when she wants — but never for the whole EU, unless she receives permission from all 28 national foreign ministers.

The other problem: Mogherini has deep reserves of soft power at her disposal, but not a single bomb or tank. On occasions like the Friday morning missile strike by the United States against a Syrian government airbase, the 43-year-old Italian’s only option was to hustle. If the EU was to have any relevance in the follow-up, Mogherini had to keep the bloc united. “Our credibility hinges on it,” she said.

Past American policymakers may have wondered, “Who do I call when I want to speak to Europe?” U.S. President Donald Trump wonders, “Why should I call Europe at all?”

Mogherini told POLITICO she spent the night on the phone with the U.S. administration and others, but the American strike — a response to a chemical weapon attack by the Syrian government — was a unilateral action from start to finish.

This time, forging consensus was “less difficult that I expected it to be,” she said. That’s because she chose to focus on “what we believe needs to be done now.” The sleepless night was followed by three hours of drafting, as national ministers nitpicked the EU position, even as their own views were hitting the airwaves.

In the end, at 2 p.m., nearly 12 hours after the missiles reached their target, Mogherini condemned the Syrian chemical attacks, described the counterstrike as “understandable” and insisted that “the EU firmly believes there can be no military solution to the conflict.” Her statement may have been carefully designed to not make waves, but it set her up to achieve, she said, a hardening of the G7 position against the Syrian government three days later, when the group’s foreign ministers met in Italy.

Mogherini’s late-night phone calls took place as she approaches the half-way point of her term as high representative of the European Union for foreign affairs and security policy and vice president of the European Commission. POLITICO spoke to 20 foreign policy practitioners — ministers, academics and members of her staff — to assess her performance so far.

EU global strategy

Grade B

Degree of difficulty: Low

The strategy Mogherini crafted for the EU contains the best and worst of the bloc’s self-image. On the plus-side, it’s the first time since 2003 that the EU has a strategy. On the downside, much of it reads like wishful thinking.

In that world, Europe is No. 1 again: the biggest economy and foreign investor, the most generous donor, the most daring free-trader. As Mogherini told POLITICO, “Sometimes I think the world would collapse if we suspended all the [EU’s] soft power activities.”

As a rules-based world order flowers around it, the strategy pitches the Union as a “connector, coordinator and facilitator,” welcomed by others because “this is no time for global policemen and lone warriors.” Published in June 2016, the strategy clearly did not predict Donald Trump.

“The challenge for the rest of her term — and very possibly for who comes after her — is finding hard power to match the soft power”

And yet, for all its faults, Mogherini’s efforts here have been generally lauded. She could have retreated after Brexit. Instead, she pushed out the strategy against internal objections just days after the vote. “The strategy is very, very good on paper,” said one MEP on the European Parliament’s Foreign Affairs committee.

The challenge for the rest of her term — and very possibly for who comes after her — is finding hard power to match the soft power.

Iran

Grade: A

Degree of difficulty: High

When Mogherini led an all-female team of negotiators, including her close adviser Helga Schmid, to seal the Iran nuclear deal in mid-2015, it was the most significant nuclear de-escalation in a generation — and a validation of the EU’s decision to establish its own diplomatic corps.

More than any other achievement in her term, this is where soft power met hard power.

The Western world trusted the EU to secure its interests. In landing the deal, Mogherini may have been standing on the shoulders of her predecessor, Catherine Ashton, but she and her team did enough to be singled out for praise by then-U.S. President Barack Obama in a call to Mogherini.

“It was a complex deal, more than 100 pages,” she said. “The writing of the deal itself was mainly in the hands of the European Union team of 15 people, no more than that.” With the Iranian diplomatic ice age over, Mogherini bragged in the Guardian in early 2017 that “trade between the EU and Iran has risen by a staggering 63 percent over the first three-quarters of last year.”

Coordinating EU policy

Grade: B+

Degree of difficulty: Moderate

In addition to herding the EU’s foreign policy ministers, Mogherini must navigate the three institutions that face the Schuman roundabout in Brussels’ soulless EU quarter. While most chief diplomats have better things to do than spend eight hours answering the questions and petting the egos of Members of Parliament, Mogherini recently did just that. She regularly logs in hours in Strasbourg and Brussels that leave MEPs impressed — and slightly worried — by her dedication.

“Maja Kocijančič, Mogherini’s spokesperson, said there is now “much stronger coordination” between the Commission and other parts of the EU, thanks to Mogherini”.

In contrast to Ashton, who was a regular no-show at European Commission meetings and was not in charge of any commissioners, Mogherini chairs meetings of foreign and defense ministers, the European Defense Agency, and a group of commissioners who report to her. These include the powerful Trade Commissioner Cecilia Malmström, as well as commissioners for development, humanitarian aid and the EU neighborhood.

Her diplomats are spread across 140 locations around the world, and increasingly include national diplomats — not just a pool of EU officials. Mogherini has also restructured the EU’s diplomatic service, introducing, for instance, a team dedicated to migration, a subject that had previously been only the Commission’s domain.

Maja Kocijančič, Mogherini’s spokesperson, said there is now “much stronger coordination” between the Commission and other parts of the EU, thanks to Mogherini: “Now, there is a real political steer and a lot more forward planning.”

Communication

Grade: A

Degree of difficulty: Low

If Mogherini were to be graded on a curve against her predecessor, she’d hit the highest marks in this area. Each person interviewed by POLITICO cited her communication skills as a major advantage over Ashton. “She understands communications and is political about it,” said one member of the management team at Mogherini’s European External Action Service.

Though she has been criticized for a tendency to stick to her comfort zone — Italians and the Italian media — she has delivered her message in 182 cities in 72 countries thus far. “Sometimes she looks a bit tired. I would be, too, if I had her schedule,” said one MEP.

Like Ashton, Mogherini has had to overcome a strikingly gendered tone in how some in the foreign policy world react to her. Several of the men interviewed by POLITICO — and only the men — commented that she “always correct, but rarely warm” or “very good on camera, but cold.”

A member of her team pointed out that she is often the only woman at the table when negotiating.

One of Mogherini’s rare female counterparts, Argentina’s foreign minister, Susana Malcorra, has only praise for how she navigates. “Her soft-spoken manner has allowed her to forcefully push for compromise when needed and to be the voice of conscience when required. Federica has mastered the difficult balance between these seemingly competing tracks,” she said.

Migration, especially the recent flood of refugees into Jordan, Turkey, Lebanon and on into the EU, is a messy policy area. Mogherini is one of the few leaving a mark, with a push to pay more attention to what’s happening outside the bloc’s borders.

While the Commission has pushed — and largely failed — with internal policies such as relocation and resettlement of refugees across the bloc, Mogherini has had some success with external efforts. “She managed to move the conversation away from purely border security issues to also cover root causes,” said one European diplomat.

“A recurring theme in reports and statements issued by Mogherini is the need for integrated multi-dimensional policies”.

The approach begins with the EU-Turkey deal limiting migration flows, but its key test will be whether the EU’s new “migration compacts” with African countries do anything to change the root causes of migration, including local conflicts and opportunities, the effects of climate change and the prevalence of people smugglers.

A recurring theme in reports and statements issued by Mogherini is the need for integrated multi-dimensional policies. “We invest in strong societies, not in strong men,” reads one line in the EU’s global strategy. If Mogherini fails, it will likely mean more migration nightmares for Europe.

Defense cooperation

Grade: B+

Degree of difficulty: Moderate

This is an area where Mogherini’s realism shines through. As tabloids bicker over whether there should be an EU army, she has moved the debate elsewhere.

Six months after the launch of her global strategy, Mogherini had won agreement from the EU’s 28 national leaders to a defense cooperation package that will see coordinated procurement and the possibility of military missions commanded from Brussels. “Eighteen months ago —forget it, it just wouldn’t fly,” admitted one impressed diplomat. “But she has that knack.”

From her earliest statements — Mogherini’s first press conference in the job was a joint appearance with NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg — her signal has been clear: The EU and NATO must be inseparable, and must share responsibility for hybrid threats like cyber warfare.

A NATO official familiar with the pair’s relationship said Stoltenberg and Mogherini have an excellent rapport dating back to their time in the youth wings of their respective socialist parties. On occasion, they even dial into each other’s meetings with third parties to demonstrate how united they are.

They’ll need to be. With Trump breathing down the neck of both the EU and NATO, they will have to work together to not fall foul of the hard power that ultimately guarantees European security.

The Balkans

Grade: D+

Degree of difficulty: Moderate

Though Mogherini has expressed fears that Russia and Turkey are turning the Balkans into a chessboard, she made limited efforts to directly engage with the region’s leaders until late 2016, leaving that task largely in the hands of Commissioner Johannes Hahn.

While Ashton was happy eking out progress on the low-profile spats that characterized relations in the region from 2009 to 2014, Mogherini stands accused of half-heartedness. Matters slid to the point that she was booed by nationalist Serbian lawmakers on her most recent visit.

On that three-day, six-nation Balkan tour, Mogherini also proved she can be clumsy with language when she said, “there is no other power in the world that has so much impact for good on the western Balkans, and that is the European Union.”

“I was happy it was on the European Council agenda last month. We need that level of engagement” — Mogherini on the Balkans

One Bosnian diplomat, a survivor of the Sarajevo siege, described his reaction to her comments: “I threw up a little.” The EU played a role in the Balkans in the 1990s, he said, that of “passive observer,” as nations butchered each other on its doorstep.

Mogherini says managing the EU’s Balkan relationships is a team effort that will only work if national governments do their bit. “I have personally pushed a lot for a collective European Union attention to the region,” she said. “I was happy it was on the European Council agenda last month. We need that level of engagement.”

Russia

Grade: C –

Degree of difficulty: High

Critics reserve their harshest words for Mogherini on Russia, accusing her of appeasing the Kremlin to preserve a chance at regime change and peace in Syria.

Central and Eastern Europeans are most vocal about the complaint: “Mogherini completely fails to address a threat more than a dozen EU member states see as a major danger,” said Jakub Janda of European Values Think Tank, a Prague-based group. Given Russia’s belligerence in Ukraine and its efforts at election meddling and disinformation, Mogherini should be taking Russia head-on, critics charge.

Mogherini and her team say she is juggling other dynamics — including EU governments at risk of going wobbly on renewed sanctions — and count holding the line as a victory against the odds. When the bloc’s unity threatened to collapse in 2016, she got the EU’s governments to agree orally to five principles to guide relations with Moscow and managed to keep sanctions in place.

Mogherini works to counter Russian propaganda with a team of experts who tweet out evidence of media manipulation. Her team says they’ve never received so many requests for information from allies about how to replicate an EU policy initiative, and that it’s this initiative — rather than the absence of finger-wagging by Mogherini — that should be used to judge whether her approach is a success.

Syria

Grade: D

Degree of difficulty: High

No foreign power looks good on Syria. That’s the opportunity and the problem. Whether it is Syria’s links to terrorism, refugees, Russia or Turkey, the seemingly intractable conflict is the third rail of Mogherini’s policy realm: dangerous and with no end in sight.

Mogherini has been carefully working on the parts of a Syrian solution she can influence: trying to maintain the skeleton of a functioning economy and civil society among Syrians (those displaced and those still in the country), protecting the unfortunate who have fled and keeping the door open for a negotiated political transition.

Last week’s Syria conference in Brussels — wedged between a Syrian chemical attack and a U.S. missile strike — was proof that for all her efforts, the EU remains at the mercy of unilateral hard power.

Still, Mogherini will not budge on her view that there can be no military solution to the conflict. Only “accountability within the U.N. system” will bring lasting change, she said. “We are the humanitarian player” on the ground in Syria, with €9.4 billion invested so far. The EU, she added, is over-delivering on its aid promises.

For Mogherini herself, the stakes couldn’t be higher. The conflict in Syria is likely to be the defining crisis of her tenure. If she is able to deliver progress on a solution, or even bring Moscow and Washington to a shared position, she will be remembered as a great EU diplomat. And if she’s not, Syria is likely to be what she’s remembered for anyway.

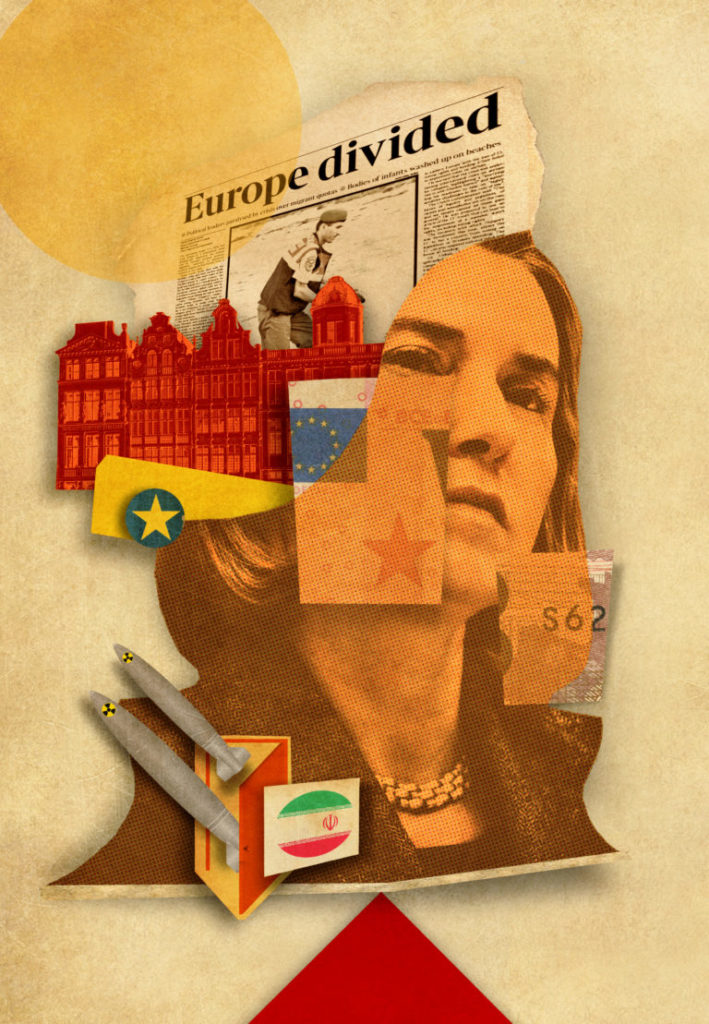

This article was updated to correct Jakub Janda’s employer. Stephen Brown contributed reporting | Illustration by Peter Horvath for POLITICO